Stuart Hall and the 6 Shades of Emojis-Which shade will you pick?

“Everyday and mundane elements of our lives can affect the person we become and be an accurate barometer for social change.” -Stuart Hall (Akomfrah)

The mundane goes unnoticed. It is commonplace. It is everyday. It is dull. But just because something is seemingly etched into the everyday routine of our lives does not mean it is not worth further critical analysis or discourse. Stuart Hall recognized this and even went a step further to consider how the everyday aspects of popular culture affect us and are linked to power and the politics of representation. Through the use of the written word, audio, and visual image this paper will give a brief biographical look at the life of cultural theorist Stuart Hall, discuss the context in which his work was written, and advocate for its contemporary relevance through the analysis of the emoji diversification phenomenon, specifically the creation of the six different shade preferences option. This paper will be accompanied by a Miles Davis soundtrack. The music attempts to viscerally affect the reader’s experience of this paper and act as an entry point to understanding the mind of Stuart Hall outside of the written word.

Hall’s theory of representation will be the foundation for the critical analysis within this paper. This theory will be used to assess the discourse around the new emoji shades and will be critiqued against the colorblind social theory. Beyond attempting to present the value of Stuart Hall’s work, this paper aims to highlight the significance the seemingly mundane play in mirroring the social climate.

Stuart Hall, background and context-Understanding the man behind the theories

In a conversation on BBC radio with Sue Lawley, Stuart Hall cites modern jazz as a major influence in his life. He states,

On first listening to modern jazz as a young student in Jamaica I listened to a lot of kinds of music, my brother played 40s American swing, we used to play Jamaican folk music, but none of that music belonged to me. The first musical sound that I felt really belonged to me was the sound of modern jazz. It opened up a new world. I knew that it was a world from the margins. It opened up the possibility of really experiencing modern life to the full, and it formed in me the aspiration to go and get it, wherever it was. (Hall 2014)

He goes on to specifically highlight the music of Miles Davis. He states, “I would say Miles Davis put his finger on my soul. The various moods of Miles Davis have matched the evolution of my feelings. They continue to be a regret for the loss of a life that I might have done lived but didn’t live” (Hall 2014). Stuart Hall’s articulation of the importance modern jazz and the music of Miles Davis played in his life is a direct example of the importance of popular culture. The artefacts within popular culture help to create a sense of belonging and identity for a person in a world that is chaotic and complex. The importance of this feeling of belonging and representation will be highlighted again later on in the paper. For now, press play on Summertime and be transported into this evolution of feelings.

☀️☀️😎 (Summertime)

Stuart Hall was born in Kingston, Jamaica on February 3,1932. He was raised in a middle class family in Jamaica, while it was still under British colonial rule. Having Scottish, African, Portuguese Jew heritage and being the darkest one in his family gave Hall a first hand experience in relation to the ways race, class, and caste operate, dictate, and marginalize the lives of people of colour. Seeing this disparity and prejudice throughout his country and it even being further perpetrated by his parents, helped to shape Hall’s critique of the world around him. Stuart Hall brought this critical point of view with him while he was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, where he cofounded two journals The New Reasoner and New Left Review. The culture shock Hall encountered after going from living in Jamaica to studying in the epicentre of Britishness, Oxford University, drove him to take an eager interest in politics and specifically politics regarding the colonised. Hall (2014) describes this culture shock when he states:

What I realised the moment I got to Oxford was that someone like me could not really be part of it. I could make a success there. I could even be part accepted into it. But I would never feel it was my place…it is the summit of something else, it is distilled Englishness, it’s the peak of the English education system. An Oxford education works only because you already know 90 per cent of it in your bones. You absorb the culture. You can’t learn those things. I could study English literature, but the cultural buzz that made each text live as part of a whole way of life, was just not me, just not me.

Luckily Hall was able to find a place amongst the academic journal community. Being an editor of the New Left Review gave Hall a platform for discourse and debate and helped to further shape Hall’s democratic, socialist anti-imperialistic politics (Akomfrah 2014).

His background and politics were prompters that led Hall to engage in a critical discourse around culture, leading to him being influential in the founding of cultural studies. Terry Eagleton (1996) describes Hall’s road to cultural studies like this, “Reading the world in terms of culture is a familiar habit of the colonial subject; but it is also an occupational hazard of the metropolitan literary intellectual, and Hall happened to be both.” Finding a balance between one’s background and intellectual curiosity is no easy feat, and although the work of Stuart Hall is highly celebrated, Eagleton does manage to articulate some qualms against this beloved cultural theorist. Eagleton (1996) states, “he is less an original thinker than a brilliant bricoleur, an imaginative reinventor of other people’s ideas.” Although Hall’s theories do bridge on the work of someone like linguist and semiotician, Ferdinand de Saussure, or cultural theorist, Raymond Williams, it is fitting that Hall is a “brilliant bricoleur” because bricolage, the construction or creation from a diverse range of things (dictionary.com), is in essence what the work of cultural studies looks at unpacking. Eagleton (1996) goes on to critique Hall when he describes Hall’s career as, “chameleon-like career can be read just as plausibly in terms of consistency as of fashionability.” Eagleton clearly has qualms with the shifting of Hall’s politics, but I would argue that what makes the work of Stuart Hall valuable and important still to contemporary analysis is that Hall continued to not just question the world around him, but also his own theories.

The work of Stuart Hall created a foundation for analysis, and it does not say this is the way you should critique or this is how you should view the world. Rather it prioritises the importance of discourse and discursive analysis. The work of Hall equips other academics to be “brilliant bricoleurs,” to use his theories as a foundation to branch off into deeper critical analysis. The work of Hall does extend beyond the field of cultural studies, but this paper will solely focus on his work within that field.

Press play: 👁🙇🏾4️⃣👤 (I Waited for You)

Cultural studies, the foundation

Cultural studies sees the politics of the invisible. Not invisible in the literal sense of the word, but similar to Ralph Ellison’s personification of the invisible man, that which others refuse to see. It is a critical analysis of the everyday, that seeks to analyse the why behind the daily stimulus people receive. Hall (1992: 11) describes it as, “ a place of necessary tension and change.” This tension and change are manifested due to the difficult notions that cultural studies brings forth. To figuratively describe it cultural studies is anti-disneyfication, it removes the happily ever after, silences the singing animals and asks the question, “Why are Disney villains usually the darkest character in the film?” Hall (1992: 12) describes the analysis of cultural studies as “an act of critical reflection, which is not afraid to speak truth to conventional knowledge, and turned on the most important, most delicate, and invisible of objects: the cultural forms and practices of a society, its cultural life.” This critical reflection is important because it puts both what is being consumed and the consumer into direct dialogue with one another. The consumer must address the conventional knowledge that he or she is surrounded by and possibly ascribes to (darkness is symbolic of something that is bad or dangerous) and reflect on what is being perpetuated by the object he or she is consuming (if it is bright or white it must be right). Hall (1992: 11) describes this direct dialogue when he states, “Cultural studies, wherever it exists, reflects the rapidly shifting ground of thought and knowledge, argument and debate about a society and about its own culture. It is an activity of intellectual self-reflection” . This intellectual self-reflection prompts questions of why and further consideration around how power is operating and functioning.

In order to grapple with the concepts within cultural studies one first must understand, “What is culture?” That is in no way an easy question to answer, and many cultural theorist have different ways of answering that question. Theorist Raymond Williams (1989: 95) claims, “culture is ordinary.” Although this answer may seem to lack complexity it hits the heart of the ethos of cultural studies. It is an examination of the ordinary things that make up our everyday. Williams (1989: 96) goes on to say, “A culture is common meanings, the product of a whole people, and offered individual meanings, the product of a man’s whole committed personal and social experience.” Williams expounded articulation around culture is similar to how Stuart Hall frames his definition of culture. “Culture is concerned with the production and the exchange of meanings-the giving and taking of meaning-between the members of a society or group” (Hall 1997: 2). These exchanges of meaning and meaning making happen on a daily basis. Culture is everywhere and is an essential part of how people define themselves and create their politics. Although studying the ordinary may seem to lack the same intellectual prowess as studying graphene, the strongest, most flexible and conductive material known to man, cultural studies is still a viable and pertinent field. The work of Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall will always be relevant because unlike graphene, culture cannot be replaced with the newest more flexible and more conductive material. Culture is here to stay, and something with that type of longevity definitely needs to be critiqued and analysed.

Press play: 😂💘💝💋 (My Funny Valentine)

Representation, language and the mundane

A critical piece within the field of cultural studies is understanding the importance of language. Cultural studies sees language as “one of the ‘media’ through which thoughts, ideas and feelings are represented in a culture. Representation through language is therefore central to the processes by which meaning is produced” (Hall 1997: 1). It is important to note that within cultural studies the word language is used in a much broader sense. “The writing system or spoken system of a particular language are both obviously ‘languages.’ But so are visual images, whether produced by hand, mechanical, electronic, digital or some other means, when they are used to express meaning” (Hall 1997: 18). A contemporary example of visual images operating as a language are emojis. Writer for New York magazine Adam Sternbergh describes emojis as “a secret code language made up of symbols that everyone intuitively understands.” Take for example this emoji:

http://emojipedia.org/aubergine/

What looks like an eggplant now means so much more when sent via text or in a tweet. The emoji language has rapidly transformed over the past three years. In 2013 Rob Speer wrote, “Three years ago [ie in 2010], these characters didn’t exist, but they’ve been adopted so quickly that on Twitter, they’re now more common than hyphens.” However, sending symbols within a message is not something that millennials can take credit for. From wingdings to XOXO and :), signs and symbols have been available forms of communication. The word emoji is “a Japanese neologism that means, more or less, ‘picture word’” (Sternbergh 2014). These 12 by 12 pixel grid images were invented by Shigetaka Kurita in the late 1990’s. In order to differentiate NTT Docomo’s pager service, Kurita created approximately 176 symbols, he called emojis. The use of the emojis left the pager world and entered the land of the smartphone in 2011. Apple put an emoji keyboard in iOS 5 in order to increase the iPhone’s popularity in the Japanese market (Sternbergh 2014). Housed between Dutch and Estonian lied a secret language waiting to be discovered by the general public.

Screenshot from iPhone Kyli Singh; http://mashable.com/2014/06/17/emoji-on-ios/

Screenshot from iPhone Kyli Singh; http://mashable.com/2014/06/17/emoji-on-ios/

Word spread or rather emojis spread like rapid fire as friends showed other friends how they were able to send the funny stickers within their messages (my younger brother showed me). With the spread of the use of emojis came the problem, not all phones could recognize the code used to display emojis. Instead of sending a heart and a kissy face to your significant other the phone would show a skull like or alien face, not exactly helpful in the romance department. See example below.

https://twitter.com/verge/status/585896160528826368/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

https://twitter.com/verge/status/585896160528826368/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

Luckily this dilemma was solved thanks to Unicode, “an international programming standard that allows one operating system to text from another” (Sternbergh 2014). With 722 symbols encoded in Unicode Apple and Android users were able to seamlessly send emoji filled messages just as easy as texting “where you at?” With all platforms being able to view emojis their use rate and popularity increased.

Facts about emoji use:

“Appear in 1 out of 20 tweets”(Speer 2013)

“Used More frequently than 1 in 600 characters”(Speer 2013)

“They’re also more common than the digit 5, or the capital letter V”(Speer 2013)

“They are half as common as the # symbol” (Speer 2013)

“The character ![]() alone is more common than the tilde ~”(Speer 2013)

alone is more common than the tilde ~”(Speer 2013)

With more and more users being able to access and receive emojis, the demand for new symbols increased. Users had exhausted the 722 symbols available, and started to notice that certain symbols were missing. There was not an avocado emoji. There was not a hotdog emoji. There were not any black people emojis. Users were quick to point out via social media that all the “people” emojis or rather humanoid characters were white.

http://bossip.com/937840/about-damn-time-apple-responds-to-emoji-diversity-problem-plans-to-finally-add-black-and-brown-characters/

In actuality most of the humanoid emojis were yellow. This yellow was suppose to be neutralizing and all inclusive similar to the way the yellow smiley faces function. “Unicode Consortium-a U.S. based nonprofit organization with a Pynchonian name that rules over all things Unicode,” (Sternbergh 2014) claimed that the yellow was a “generic (nonhuman) default” (Dewey 2015). However, this was not enough for the general public. Users even went to dosomething.org to create a petition for people to sign to advocate for more “diverse” emojis. People wanted to see themselves “represented” (remember this word because we are going to come back to it). Unicode Consortium tried to remind users that its purpose was not to create emojis. Sternbergh (2014) articulates this dilemma when he states, “In order to add new emoji, Unicode would have to invent them, then design them, then approve them, and then encode them.” Vice President of Unicode, Peter Constable even stated, “The letters of English are the letters of English we don’t have people inventing new letters of English everyday” (Sternbergh 2014).

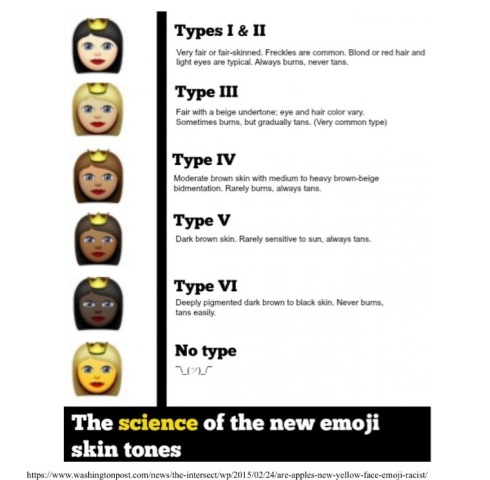

Eventually the cries for diversity were heard in 2015, when Unicode announced that 250 new symbols would be released (Sternbergh 2014). Although the term new was a bit of a stretch because most of the “new emoji were all either translations or pre-existing font sets known as wingdings and webdings” (Sternbergh 2014). But users did not let that news ruin the moment because a new feature was also included within the 250 new symbols. “The new Unicode 8.0 will modify pre existing emojis, allowing users to long-press their favourite face in order to bring up a palate of skin-tone options, a harmonious rainbow of diversity” (Davis 2014).

This “harmonious rainbow of diversity” (Dewey 2015) was derived from the FitzPatrick scale a recognized standard for dermatology (Sternbergh 2014). “FitzPatrick scale was developed by a professor at Harvard Medical School in the ‘70s to describe how different skin tones respond to ultraviolet light” (Dewey 2015). Unicode was quick to point out that the yellow option was not a part of that scale and was just a “generic (nonhuman) default,” after accusations of racism occurred when users saw the yellow face as a slight against the Asian community (Dewey 2015).

Besides the continued qualms with the yellow face, when users discovered this update cheers, tweets of joy, and tears were blasted across social media. Good work finally had been done. The users voices were heard.

But like all new toys the allure only lasted for so long as users began to have a few qualms with the six shades of emoji upgrade.

As Raymond Williams (1989: 94) points out the concept of good within culture must be examined from a broader perspective,

‘Good’ has been drained of much of its meaning, in these circles, by the exclusion of its ethical content and emphasis on a purely technical standard; to do a good job is better than to be a do-gooder. But do we need reminding that any crook can, in his own terms, do a good job? The smooth reassurance of technical efficiency is no substitute for the whole positive human reference.

The “good” work done by Unicode of creating a “harmonious rainbow of diversity” (Dewey 2015) quickly started to take a turn for the worst. What was once a fun new way to communicate turned into a war of positioning, representation, and shadeism. In an article for the Washington Post Paige Tutt points out, “The emojis are being used to make racist comments on social media and insert questions of race in texts and tweets where it may never have arisen before.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/04/10/how-apples-new-multicultural-emojis-are-more-racist-than-before/

Another qualm Tutt and other users started to articulate around the new shade preference option was, “instead of creating actual emojis of colour, Apple simply allows its users to make white emoji a different colour”. Tutt goes on to describe this hue selection as a “bastardized emoji blackface.”

This unrest around the 6 shades of emoji is a prime example of how Stuart Hall’s theory of representation is still contemporarily relevant. Hall (1997: 19) states, “Visual signs and images, even when they bear a close resemblance to the things to which they refer are still signs: they carry meaning and thus have to be interpreted.” In forming a critical analysis around the six shade emoji phenomenon there are two approaches available for analysis, the semiotic approach and the discursive approach. Hall (1997: 6) explains the difference in the two approaches when he states, “the semiotic approach is concerned with the how of representation, with how language produces meaning-what has been called its ‘poetics,’ whereas the discursive approach is more concerned with the effects and consequences of representation-its ‘politics’.” Although the semiotic approach could easily be applied to understanding the six shades of emoji because emojis are indeed symbols, which is at the core of semiotics. The discursive approach looks more at the why which is where the theories of Stuart Hall are more easily housed. Hall (1997: 6) goes on to describe the discursive approach when he states, “It examines not only how language and representation produce meaning, but how the knowledge which a particular discourse produces connects to power, regulates conduct, makes up or constructs identities and subjectivities, and defines the way certain things are represented, thought about, practised and studied.”

So how can a 12 by 12 pixel grid image be linked to power, representation, and politics? That question has multiple answers, but I have deducted two. First the six shades of emoji are a representation of the on going battle between multiculturalism and colorblindness. Second the introduction of the six shades of emoji is a barometer mirroring the social climate around the Black Lives Matter Movement, similar ties between the mundane and politics have been seen throughout the past couple of decades.

To address the first answer, the concept of difference and how it is articulated through culture and popular culture must be discussed. Hall (1997: 229) states, “ people who are in any way significantly different from the majority- ‘them’ rather than ‘us’–are frequently exposed to this binary form of representation. They seem to be represented through sharply opposed, polarized, binary extremes–good/bad, civilized/primitive, ugly/excessively attractive, repelling-because-different/compelling-because-strange-and-exotic.” With this binary form of representation being the norm it then becomes hard to create a binary in 12 by 12 pixel grid with characters that are not always being used in conversation with each other. Not being able to rely on this binary of representation, the next option is to choose physical characteristics that articulate difference, which is a slippery slope that Unicode definitely did not want to walk into. Unable to use binary representation and physical characteristics, Unicode was left with colour to be the only way for “diversity” to be accessed. But as dictated above that attempt of diversity was to no avail.

This failed attempt was what colorblind theorist had been waiting for. “Color-blindness, proposes that racial categories do not matter and should not be considered when making decisions…social categories should be dismantled and disregarded, and everyone should be treated as an individual” (Richeson and Nussbaum 2004). This debacle showed what categories of race do to communities of people. They are divisive and cause stress. But before the t-shirts of “I don’t see race” are made I think it is important not to cower away from the turn of events around the six shades of emoji. Hall (1997: 238) states,

Difference is ambivalent. it can be both positive and negative. It is both necessary for the production of meaning, the formation of language and culture, for social identities and a subjective sense of the self as a sexed subject-and at the same time, it is threatening, a site of danger of negative feelings, of splitting, hostility and aggression towards the ‘other.’

Although difference can be divisive that does not mean a person’s social identity should be ignored because it can lead to stressful and uncomfortable conversations. This is a key argument within the theory of multiculturalism. “Multiculturalism, proposes that group differences and memberships should not only be acknowledged and considered, but also celebrated…ignoring ethnic group differences, undermines the cultural heritage of non-white individuals, and as a result is detrimental to the well being of ethnic minorities” (Richeson and Nussbaum 2004). This six shades of emoji debacle did not show causation to remove racial categories. Rather it highlighted the ways in which conversations about race are avoided within diverse friend groups, how the notion of racial identity being tied solely to biological skin tone is problematic, and the amount of racism that still exists within the world today. If choosing to a certain shade of emoji makes a person feel uncomfortable when he or she is speaking with friends that is an issue that needs to be addressed not avoided. Simplifying race to skin tone completely negates the culture and history. Race is not biological, rather it is socially constructed and that complexity is seen through users having problems with just selecting a shade. Racism is an uncomfortable truth, that no one should choose to ignore due to the progress that the world has made. All of these points are important and deserve further conversation rather than being hidden behind a yellow “generic (nonhuman) default” (Dewey 2015). Hall (1997: 5) highlights this importance when he states, “Without these signifying systems, we could not take on such identities (or indeed reject them) and consequently could not build up or sustain that common ‘life-world’ which we call a culture.” The formation of identity is an important aspect of our daily lives and should never be refuted in order to avoid debate.

To address the second answer, the importance of time is crucial. The increase in conversation around where are the black emojis is parallel to the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. As black bodies were being shot down and discarded, the conversation around the importance of black lives and black representation increased. The language that emoji users used around discussing their issues with the lack of representation all point to feelings of insignificance and not worthy enough to be represented. Now not all will agree with that parallel that was just made. Raymond Williams (1989: 99) states, “The second false equation is this: that the observable badness of so much widely distributed popular culture is a true guide to the state of mind and feeling, the essential quality of living of its consumers.” Although Raymond Williams would argue that the parallel is a leap, Unicode’s decision to include the six shades of emoji was definitely in response to the politics of the time. When there is a rise in social unrest no company wants to be on the wrong side of history. Unicode’s decision is not the only example of this phenomenon. Take for example the choices made by Crayola. In 1962, Crayola changed the name of the ‘flesh’ crayon to peach.

Crayola themselves even cites this decision as “partially as a result of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement” (Rudman 2011). Additionally in 1992, Crayola released multicultural crayola products. Even though Crayola says this decision was made because “kids and teachers were asking for them” (Rudman 2011). I would argue that the release parallels to the timing of the Rodney King incident and the Rodney King trial.

(Rudman 2011)

(Rudman 2011)

However the journalists on Fox and Friends have another theory than my own. In a 2011 TV segment about the multicultural markers one of the reporters stated that this decision, which was made in 1992, was nothing more than “pandering more to liberal parents,” and that the only colour Crayola is concerned about is green (Rudman 2011). I would never discount money as a motivator, but these timeline parallels in my opinion are an example of the Stuart Hall quote that opened the paper. “Everyday and mundane elements of our lives can affect the person we become and be an accurate barometer for social change”(Akomfrah 2014). The timing around these cultural objects was not a coincidence. This is an example of the everyday being a barometer in action.

Conclusion

Press play: ⚪️🕛🌃 (Round about midnight)

As the sound of Miles Davis’ trumpet reverberates against your walls, I hope it has the same level of impact that Stuart Hall has had on the field of cultural studies. Although there is room to debate some of the concepts Hall proposed, what remains undebatable is that the work of Stuart Hall helped to lay the foundation for understanding and critiquing the everyday of the world. Hall’s own life was a reflection of his work and study. The displacement he felt while at Oxford University catapulted him to ask critical questions around topics of representation, race, and identity. The theories Hall developed continue to remain contemporarily important because understanding culture and the all encompassing umbrella that it is, is no easy task. That is clearly illustrated by the commotion little 12 by 12 pixel grid emoji’s stirred over the past three years. The everyday and the mundane may on the surface seem trivial, but in the words of Paulo Freire “language is never neutral.” Even a 12 by 12 pixel grid emoji can come attached with power and politics of representation. That is why cultural studies and the work of Stuart Hall is valuable because it creates a space and a framework for this analysis. It brings the everyday or rather it brings a piece of our lives into the classroom. It no longer limits education to be nothing more than facts and figures. It shows how education can be a space for debate, discourse, and analysis.

References

Akomfrah, J., Gopaul, L., Lawson, D., Hall, S., Aukema, D., In Asuquo, N., Mathison, T., …

Time/Image (Firm),. (2014). The Stuart Hall Project.

Black Lives Matter. Retrieved from http://blacklivesmatter.com/about/.

Davis, A. (2014) Rejoice! Emoji Realizes Nonwhite People Exist. New York Magazine,

Retrieved from nymag.com/thecut/2014/11/rejoice-emoji-realizes- nonwhite-people-exist.html.

Dewey, C. (2015). Are Apple’s new ‘yellow face’ emoji racist? The Washington Post, Retrieved

from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp

/2015/02/24/are-apples-new-yellow-face-emoji-racist/.

Diversify My Emoji. Do Something, Retrieved from

https://www.dosomething.org/us/campaigns/diversify-my-emoji.

Eagleton, T. (1996) The Hippest. [Review of the book Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues.]

London Review of Books, 18(5), 3-5. Retrieved from http://lrb.co.uk/v18/no5/terry-eagleton/the-hippest.

Hall, S. (2014, Feb 20) Castaway: Stuart Hall in his own words. Open Democracy. Retrieved

from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1500443327?accountid=14511.

Hall, S. (1997) Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, London:

Sage.

Hall, S. (1992) Race, Culture, and Communications: Looking Backward and Forward at Cultural

Studies, Rethinking Marxism, 5: 1, 10-18, DOI:10.1080/08935699208657998.

Richeson, J., & Nussbaum, R. (2004). The impact of multiculturalism versus color-blindness on

racial bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(3), 417-423.

Rudman, C. (2011) Fox & Friends Outraged Crayola Recognizes More Than One Skin Tone.

Media Matters for America, Retrieved from http://mediamatters.org/blog/2011/04/07/fox-amp-friends-outraged-crayola-recognizes-mor/178446.

Speer, R. (2013). Emoji are more common than hyphens. Is your software ready? Luminoso,

Retrieved from blog.luminoso.com/2013/09/04/emoji-are-more-common-than-hyphens/.

Sternbergh, A. (2014) Smile, You’re Speaking Emoji: The rapid evolution of a wordless

tongue. New York, Retrieved from

nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2014/11/emojis-rapid-evolution. html.

Tutt, P. (2015). Apple’s new diverse emoji are even more problematic than before: Racialized

emoji insert race into texts and tweets where it never would have arisen before.

Washington Post, Retrieved from

https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/04/10/how-apples-new-multic

ultural-emojis-are-more-racist-than-before/.

Williams, R. (1989). Culture is Ordinary. Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism,

London: Verso, pp. 3-14.

This is a really vibrant piece of academic writing – I love reading your stuff because you make theory live and breathe. One thing that really jumped out for me is the contrast between ‘bricolage’ and ‘original thinking’. Whilst it is a relevant critique of Hall, the layers of judgement and status laminated into the dichotomy made me recoil. It seems that, whilst Hall was establishing his voice and methodology in academia, the academy was already judging him in terms of the status and prestige afforded to certain kinds of areas of study, methodologies, kinds of academic output – all of which links back to the issues he was wrangling with.

LikeLike